Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE)?

What is Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE)?

There is now evidence that repeated concussions could be associated with the development in later life of a particular kind of degenerative disease called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

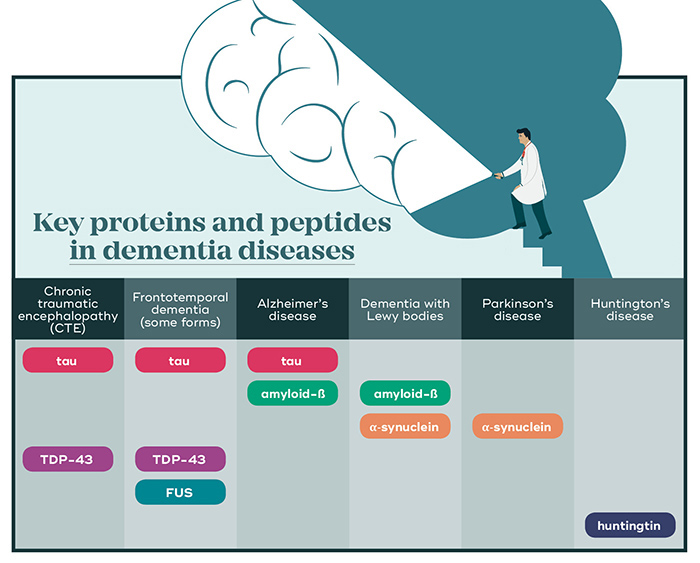

CTE is a progressive disease with Alzheimer’s-like symptoms. It was first discovered by neuropathologist Dr Bennet Omalu in the early 2000s in the brain of Mike Webster, a former National Football League (NFL) player. When Omalu looked at Webster’s brain tissue under the microscope he observed concentrations of a material known as tau. This is one of two proteins known to accumulate in the brain in Alzheimer’s disease. Since then, CTE has been found in the brains of 110 out of 111 former NFL players who donated their brains to research.

CTE has many of the same physiological hallmarks of forms of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, particularly the abnormal accumulation in the brain of a protein called tau. In a healthy brain, tau is found in the axons, the transmission lines of neurons, where it plays an important role in maintaining the structure of the internal transport system of these nerve cells. In conditions such as Alzheimer’s and CTE, tau instead forms tangles that clump together to disrupt the cells’ transport system.

These are known as 'neurofibrillary tangles' and sometimes simply 'tau tangles'. They’re a cellular signpost of a group of degenerative diseases associated with aggregations of tau protein in the brain. These clumps are thought to eventually lead to the death of neurons. As more and more neurons die and large areas of brain tissue become affected, dementia symptoms appear: memory loss, confusion, Parkinson’s-like tremors, walking problems, impaired judgement, depression and personality changes.

CTE and dementia share many symptoms and they also share two key proteins that cause toxic clump in neurons.

The need for early CTE diagnosis

Repeated head trauma doesn’t always lead to CTE and it is likely a person’s genetic background also plays a role. Currently, the only way to diagnose CTE is post-mortem, which means it’s impossible to determine how prevalent the condition is in the general population or catch the condition at an early stage.

The next challenge for researchers is to develop techniques that can identify CTE in living brains. QBI’s Associate Professor Fatima Nasrallah is using the support of a Motor Accident Insurance Commission Senior Research Fellowship to work on TBI, specifically to try and develop an early diagnostic test for concussion. She hopes to use biomarkers and imaging to develop a test that will be able to detect even subtle changes in brain function following a head injury.

CTE research brings more questions

It’s only since the early 2000s that CTE has been linked to concussion and, not surprisingly, there is still much work to be done in understanding the relationship between the two. We are, however, only just developing ways to see tau using imaging techniques such as positron emission tomography or PET. One major difficulty with studying CTE is that the only definitive way to make a diagnosis is by autopsy – looking at people’s brains after they’ve died.

We also don’t know how many or what type of concussions it takes for someone to develop CTE or how long it takes for the disorder to appear. Most importantly, we don’t know what can be done to prevent or reverse the damage.

The presence of abnormal tau tangles does offer a diagnostic and therapeutic target, just as it does in other neurodegenerative disease such as Alzheimer’s. Researchers like QBI’s Professor Jürgen Götz are exploring ways to remove the tau tangles with non-invasive ultrasound, while others are focusing on imaging techniques that can reveal tau when CTE is still in its early stages, offering a greater chance of treatment.