Concussion in sport

It’s not often a major Hollywood movie is devoted to a single medical condition. But in late 2015, the film Concussion was released, telling the story of a forensic pathologist’s attempts to shine light on the American National Football League’s hidden secret of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) – a long-term complication of repeat concussions.

The film’s release represented a peak in public attention on a condition that had previously not been discussed much outside medical circles but suddenly seemed to be worryingly common. The film is set in 2009. In the years since then, attitudes towards concussion in professional sport have come a long way. Concussion is now widely recognised as a medical issue for many sports. In many codes, it’s the team doctors who are being given the final say about if and when a player can return to play after a head injury. Most importantly, they’re being given the authority to apply medical reasoning to override the wishes of coaches and even the players themselves.

Concussion mantra: If in doubt, sit it out

Melbourne-based neurosurgeon and concussion expert Professor Gavin Davis says the general attitude to the condition just 10 years ago was that players should ‘get over it and get on with it’. Today it is no longer seen as a sign of weakness to be ruled out of play because of concussion.

In the Australian Football League (AFL), there are specific rules around head knocks, such as a mandated 20-minute period off the ground to complete a concussion medical assessment, and no return-to-play if a concussion diagnosis is made.

Professor Davis says the AFL has been ahead of the game on concussion, working with concussion experts for many years and convening a concussion working group in 2010, long before head knocks began grabbing headlines. That working group has developed guidelines to help doctors, coaches and players diagnose and manage the estimated 6–7 cases of concussion that occur per team per season across all levels of AFL competition. The key principles of these guidelines are that concussion is a complex and still poorly understood condition that needs to be managed using an individual-based approach with a number of steps, including:

- A period of rest

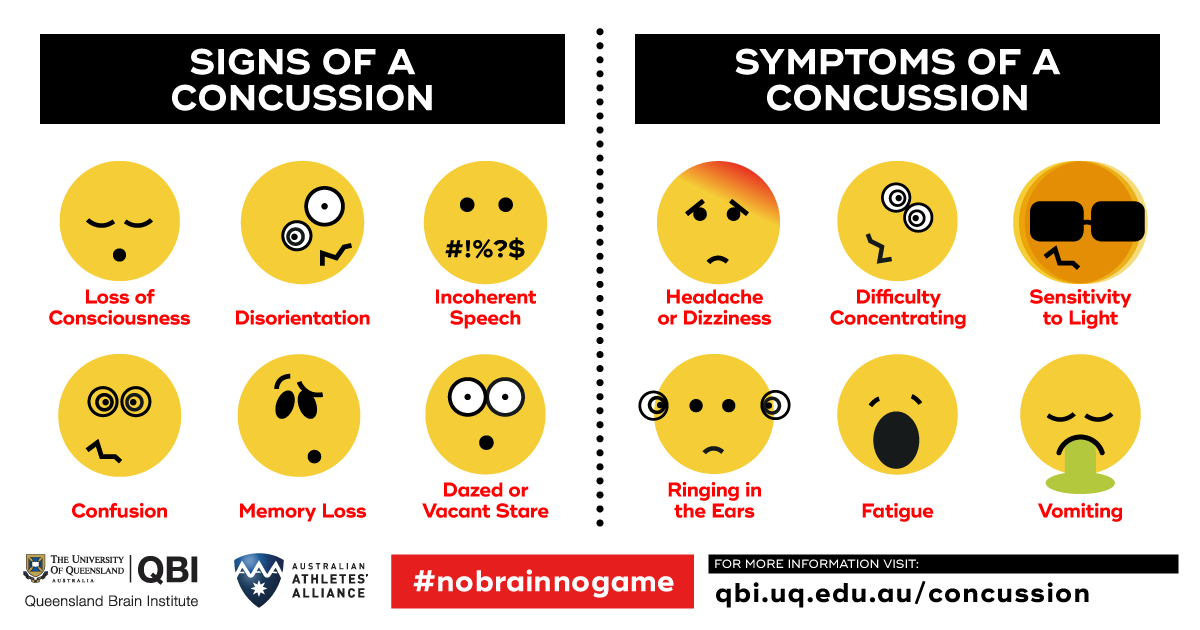

- Monitoring for ongoing or changing signs and symptoms

- Neuropsychological tests to monitor recovery

- A graduated return to activity in conjunction with monitoring

- A doctor’s OK before returning to play

These recommendations are now found in a similar form in many other sport concussion guidelines around the world. The overarching mantra, however, is ‘if in doubt, sit them out’.

Concussion: from national leagues to schools

The heightened awareness of concussion at the professional level has also filtered down to community sport, says Professor Caroline Finch, director of the Australian Centre for Research into Injury in Sport and its Prevention. Unfortunately, the messages about concussion are often mixed or misinterpreted. Some parents are so concerned about the risks and consequences that they keep their child off the sports field altogether.

Others see professional players return to the field after a head knock during a game, and assume therefore that concussion isn’t that serious. Professor Finch says concussion guidelines also apply to community sport. But without the same level of medical support that’s available to professionals, those guidelines aren’t always implemented with as much rigour. This is an issue taken seriously by many codes, some of which issue guidelines specifically targeted at the community level.