Treatments for dementia

There is no cure for dementia, and while current treatments manage symptoms, they offer no prospect of recovery. The main therapies available come in the form of medications and social programs.

Drugs for dementia

For Alzheimer’s disease, most medications aim to correct the impact to the brain’s chemical messengers – called neurotransmitters – particularly, the cholinergic and glutamate neurotransmitter systems. Drugs known as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors prevent enzymes from breaking down acetylcholine (which is important for memory), meaning more of it is available at the sites where neurons transmit messages. Cholinergic treatments may be prescribed for people with mild-to-moderate disease. Glutamate blockers prevent excess glutamate destroying neurons and are given to those with moderate-to-severe disease. There's a window for using these drugs; they can improve symptoms in some people, but because of side effects, their use is closely monitored by doctors.

Immunotherapy: vaccines for dementia

Whereas currently available medicines manage symptoms, new treatments are focused on slowing or reversing the disease process itself by using the body’s own immune defence system. This approach, called immunotherapy, involves creating artificial antibodies that attach to abnormal aggregates (such as amyloid-β or tau), and mark them for destruction by the immune system. Immunotherapy is experiencing a surge of interest and a number of clinical trials – targeting both amyloid-β and tau – are underway.

Antibody: An antibody is a large protein produced by the body’s immune system when a foreign substance (such as bacteria, viruses, or parasites) is detected. Antibodies can tag an invader for destruction by other immune cells, or directly destroy it. Antibodies can be engineered and used as research tools, in diagnostics and for therapy.

Vaccine: A vaccine is an introduced agent that trains the immune system to protect against future exposure to that agent.

Ultrasound

A major problem in treating any brain disorder is the difficulty in accessing the brain itself. Not only is the brain protected by a thick skull and a three-layered protective membrane called the meninges, but the blood-brain barrier prevents most things from leaving the bloodstream and entering the brain. While it is beneficial for keeping out foreign substances such as toxins or bacteria from the brain, the blood-brain barrier is a huge impediment to drug development for brain disorders. Not surprisingly, vast resources have been devoted to designing drugs with the right properties to get through this almost impenetrable barrier.

An alternative way to overcome the blood-brain barrier is to temporarily open it. Focusing ultrasound waves at specific locations in the brain can temporarily open the tight junctions of the blood-brain barrier that are usually sealed shut. This allows drugs to enter the brain that, because of their size or chemical properties, are normally prevented from doing so. Higher brain levels of an appropriate therapeutic drug means more of the drug reaches its target, elevating the drug’s effectiveness.

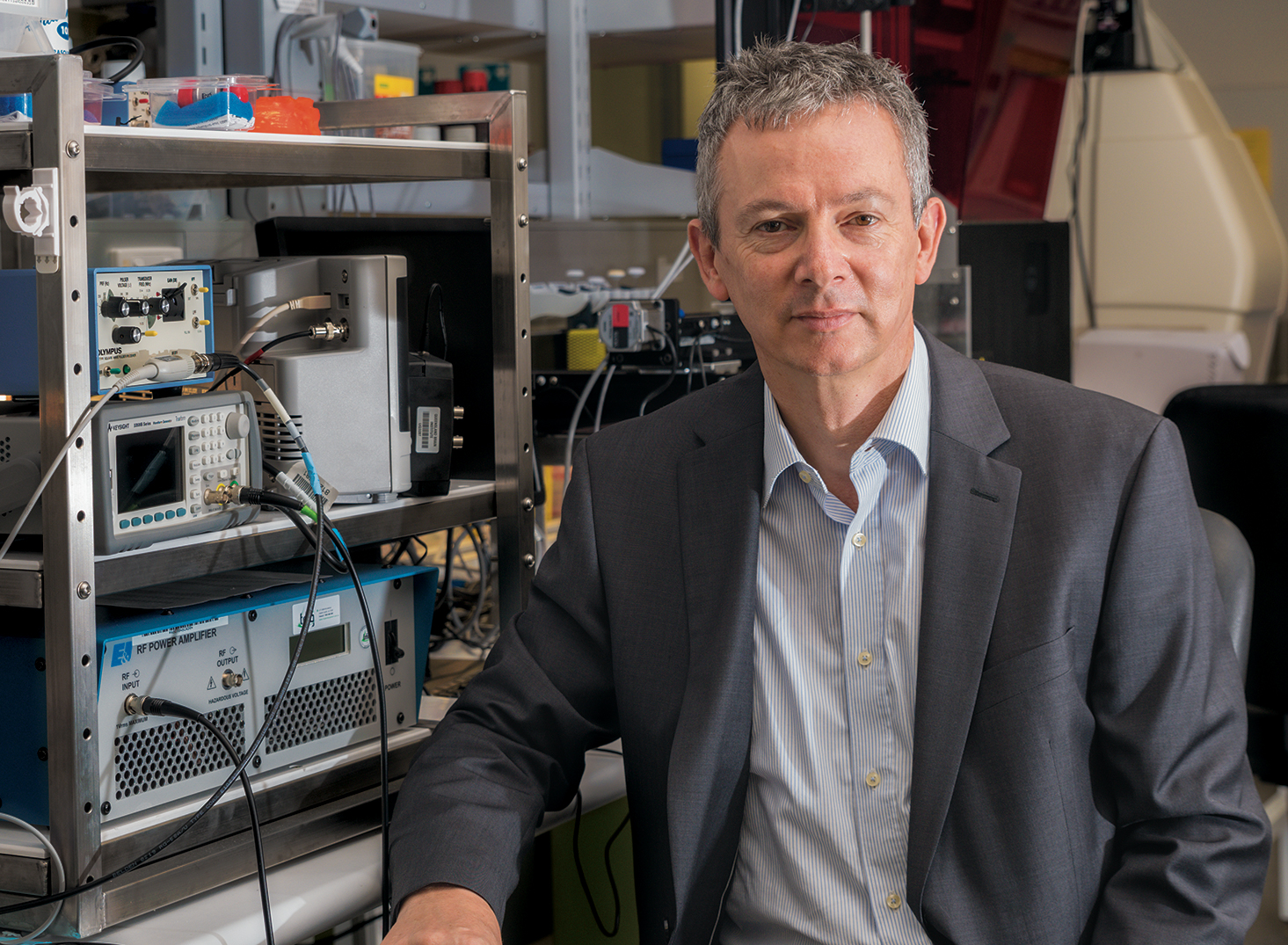

Research from the laboratory of Professor Jürgen Götz at CJCADR, established scanning ultrasound as a method to clear amyloid-ß from the brains of Alzheimer's mice and restore memory. Extending this work, he and his team have shown that scanning ultrasound helps deliver an antibody that works against the toxic tau protein.

When mice were given the tau antibody alone, the amount of toxic tau protein decreased and the animals’ behaviour improved. Multiple treatments of ultrasound on its own also decreased the levels of toxic tau, and had a positive effect on cognition when the number of treatments was increased. Most crucially, when ultrasound was combined with the antibody, the therapeutic effects were even greater. To test the safety of using ultrasound to open the blood-brain barrier, this research is moving into sheep, which have a skull thickness similar to human skulls. If successful, the next stage will be to add additional capabilities and proceed to human clinical trials.

Exercise as a treatment

Exercise may be an effective way of decreasing the risk of cognitive decline. Evidence for its direct benefit as a treatment for dementia, however, is lacking. A 2015 review, which analysed multiple studies into the effects of exercise on people with pre-existing dementia, found some evidence that exercise could help with daily living activities, but no clear cognitive benefits were found. Other studies show that people who exercise regularly are less likely to have dementia.

QBI Founding Director Professor Perry Bartlett successfully used exercise to improve cognition in older mice. He is now leading a human clinical trial, along with researchers from the UQ School of Human Movement and Nutrition Sciences and the Centre for Advanced Imaging, to find the amount, intensity, and type of exercise that might lead to cognitive improvement in elderly people. It’s thought that exercise boosts the production of new neurons in the brain, which might improve cognition.

Social programs

Keeping loved ones active with hobbies and interests they enjoyed in the past can be important after a disease diagnosis. Social programs such as music therapy and visits with animals can help stir memories, foster emotional connections with others, lessen anxiety and irritability and make people feel more engaged with life.