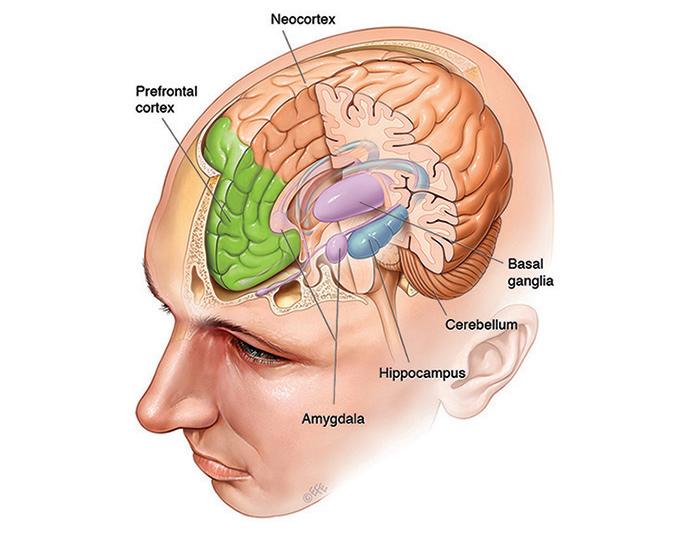

Where are memories stored in the brain?

Memories aren’t stored in just one part of the brain. Different types are stored across different, interconnected brain regions. For explicit memories – which are about events that happened to you (episodic), as well as general facts and information (semantic) – there are three important areas of the brain: the hippocampus, the neocortex and the amygdala. Implicit memories, such as motor memories, rely on the basal ganglia and cerebellum. Short-term working memory relies most heavily on the prefrontal cortex.

Explicit memory

There are three areas of the brain involved in explicit memory: the hippocampus, the neo-cortex and the amygdala.

Hippocampus

The hippocampus, located in the brain's temporal lobe, is where episodic memories are formed and indexed for later access. Episodic memories are autobiographical memories from specific events in our lives, like the coffee we had with a friend last week.

How do we know this? In 1953, a patient named Henry Molaison had his hippocampus surgically removed during an operation in the United States to treat his epilepsy. His epilepsy was cured, and Molaison lived a further 55 healthy years. However, after the surgery he was only able to form episodic memories that lasted a matter of minutes; he was completely unable to permanently store new information. As a result, Molaison’s memory became mostly limited to events that occurred years before his surgery, in the distant past. He was, however, still able to improve his performance on various motor tasks, even though he had no memory of ever encountering or practising them. This indicated that although the hippocampus is crucial for laying down memories, it is not the site of permanent memory storage and isn’t needed for motor memories.

The study of Henry Molaison was revolutionary because it showed that multiple types of memory existed. We now know that rather than relying on the hippocampus, implicit motor learning occurs in other brain areas – the basal ganglia and cerebellum.

Neocortex

The neocortex is the largest part of the cerebral cortex, the sheet of neural tissue that forms the outside surface of the brain, distinctive in higher mammals for its wrinkly appearance. In humans, the neocortex is involved in higher functions such as sensory perception, generation of motor commands, spatial reasoning and language. Over time, information from certain memories that are temporarily stored in the hippocampus can be transferred to the neocortex as general knowledge – things like knowing that coffee provides a pick-me-up. Researchers think this transfer from hippocampus to neocortex happens as we sleep.

Amygdala

The amygdala, an almond-shaped structure in the brain’s temporal lobe, attaches emotional significance to memories. This is particularly important because strong emotional memories (e.g. those associated with shame, joy, love or grief) are difficult to forget. The permanence of these memories suggests that interactions between the amygdala, hippocampus and neocortex are crucial in determining the ‘stability’ of a memory – that is, how effectively it is retained over time.

There's an additional aspect to the amygdala’s involvement in memory. The amygdala doesn't just modify the strength and emotional content of memories; it also plays a key role in forming new memories specifically related to fear. Fearful memories are able to be formed after only a few repetitions. This makes ‘fear learning’ a popular way to investigate the mechanisms of memory formation, consolidation and recall. Understanding how the amygdala processes fear is important because of its relevance to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which affects many of our veterans as well as police, paramedics and others exposed to trauma. Anxiety in learning situations is also likely to involve the amygdala, and may lead to avoidance of particularly challenging or stressful tasks.

QBI researchers including Professor Pankaj Sah and Dr Timothy Bredy believe that understanding how fear memories are formed in the amygdala may help in treating conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder.

Implicit memory

There are two areas of the brain involved in implicit memory: the basal ganglia and the cerebellum.

Basal ganglia

The basal ganglia are structures lying deep within the brain and are involved in a wide range of processes such as emotion, reward processing, habit formation, movement and learning. They are particularly involved in co-ordinating sequences of motor activity, as would be needed when playing a musical instrument, dancing or playing basketball. The basal ganglia are the regions most affected by Parkinson’s disease. This is evident in the impaired movements of Parkinson’s patients.

Cerebellum

The cerebellum, a separate structure located at the rear base of the brain, is most important in fine motor control, the type that allows us to use chopsticks or press that piano key a fraction more softly. A well-studied example of cerebellar motor learning is the vestibulo-ocular reflex, which lets us maintain our gaze on a location as we rotate our heads.

Working memory

Prefrontal cortex

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is the part of the neocortex that sits at the very front of the brain. It is the most recent addition to the mammalian brain, and is involved in many complex cognitive functions. Human neuroimaging studies using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machines show that when people perform tasks requiring them to hold information in their short-term memory, such as the location of a flash of light, the PFC becomes active. There also seems to be a functional separation between left and right sides of the PFC: the left is more involved in verbal working memory while the right is more active in spatial working memory, such as remembering where the flash of light occurred.