Can you grow new brain cells?

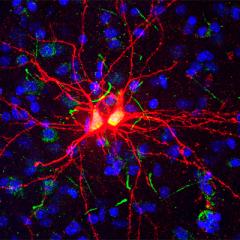

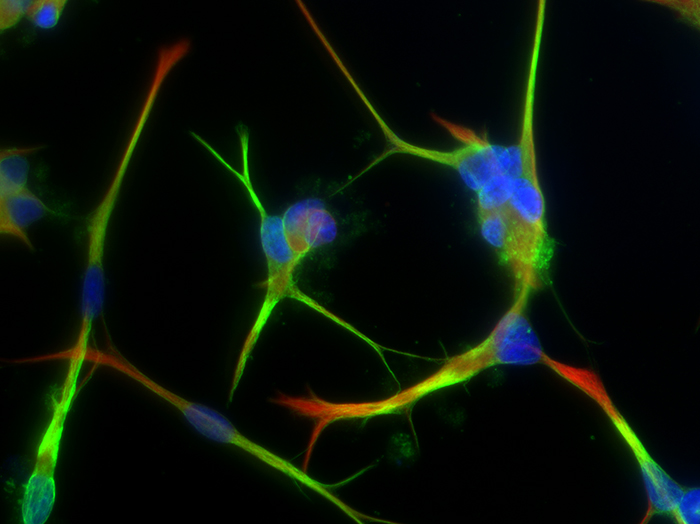

Brains are incredibly adaptive organs. Our brain cells (neurons) and the connections between them are constantly changing, which enables us to learn and remember, acquire new skills, and recover from brain injury.

It's a property referred to as 'neuroplasticity' – the ability of the brain and nervous system ability to remodel in response to new information, whether that be due to experiences, behaviour, emotions, or injury.

One of the methods the brain does this is through a process known as neurogenesis – the creation of new neurons. Neurogenesis is a particularly important process when an embryo is developing. Until only recently, it was thought that the number of neurons we're born with is fixed – that the central nervous system, including the brain, was incapable of neurogenesis and unable to regenerate.

The brain can produce new cells

But neuroscientists led by QBI's founding director, Professor Perry Bartlett, discovered stem cells in the hippocampus of the adult brain in the 1990s. Because stem cells can divide, and differentiate into many types of cells, the game-changing discovery suggested that neurogenesis could hold the key to treating conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Neurogenesis is now accepted to be a process that occurs normally in the healthy adult brain, particularly in the hippocampus, which is important for a learning and spatial memory. Damage to the hippocampus can lead to difficulties with navigation, as Dr Lavinia Codd found when, at age 31, she had a stroke that damaged her right hippocampus.

Earlier this year, QBI researchers made the world-first discovery that new adult brain cells are also produced in the amygdala, a region of the brain important for processing fear and emotional memories.

The amygdala, an ancient part of the brain, is important for attaching emotional significance to memories, and also plays a key role in fear learning, which causes us to learn that an experience or an object is frightening.

“Fear learning leads to the classic flight-or-fight response – increased heart rate, dry mouth, sweaty palms – but the amygdala also plays a role in producing feelings of dread and despair, in the case of phobias or PTSD, for example,” says lead researcher Dr Dhanisha Jhaveri.

Disrupted connections in the amygdala are linked to depression, and anxiety disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and the hope is that the discovery could lead to new treatments for these conditions.

“Finding ways of stimulating the production of new brain cells in the amygdala could give us new avenues for treating disorders of fear processing, which include anxiety, PTSD and depression,” says Dr Jhaveri. The discovery shed further light on the brain's ability to change and adapt, and further research will look at understanding the function of new cells in the the amygdala.

Stimulating the growth of new brain cells

As the brain ages, our ability to learn and remember gradually declines. It's thought that these changes in memory occur as a result of decreased neurogenesis – that stem cells in regions such as the dentate gyrus, in the hippocampus, lose their ability to produce new neurons. The hippocampus is known to shrink with age.

But it's not all bad news – these changes aren't necessarily permanent. "While you can get shrinkage in hippocampus, there is certainly evidence now that you could change that – reverse that shrinkage and reverse any loss of learning in memory by stimulating both the production of these new nerve cells, but also stimulating greater connectivity within the hippocampus," says Professor Perry Bartlett.

He and Dr Daniel Blackmore have found in mice that exercise is able to increase production of new brain cells and improve learning and memory in the ageing brain. They are now heading up a clinical trial monitoring 300 people aged 65 and older to identify the right amount, intensity and type of exercise that leads to cognitive improvement.

“Ultimately, we would hope to have clear public health guidelines as to how exercise can both prevent and reverse dementia," says Professor Bartlett.