Podcast: Mia Freedman on living with anxiety

Mia Freedman is the founder and director of the Mamamia Women's Network and seems to have it all together. But here she talks openly, to QBI Chairperson, Sallyanne Atkinson AO, about her personal struggle with anxiety, how she was convinced she had a non-existent cancer, and when her world came tumbling down.

Mia Freedman is the founder and director of the Mamamia Women's Network and seems to have it all together. But here she talks openly, to QBI Chairperson, Sallyanne Atkinson AO, about her personal struggle with anxiety, how she was convinced she had a non-existent cancer, and when her world came tumbling down.

Transcript

Sallyanne: Hi! You’re listening to a Grey Matter. The neuroscience podcast from the Queensland Brain Institute at the University of Queensland. I'm Sallyanne Atkinson. I’m chair of the QBI's advisory board and I’m your guest host for this episode.

At one point or another, we've all experienced stress. It may have been in the form of a work deadline, an upcoming exam or perhaps moving house, one of the most stressful things of all. But when anxious feelings persist beyond a stressful situation, it may not be just a passing worry. Anxiety, is Australia’s most common mental condition. On average one in four people will experience it at some stage in their life.

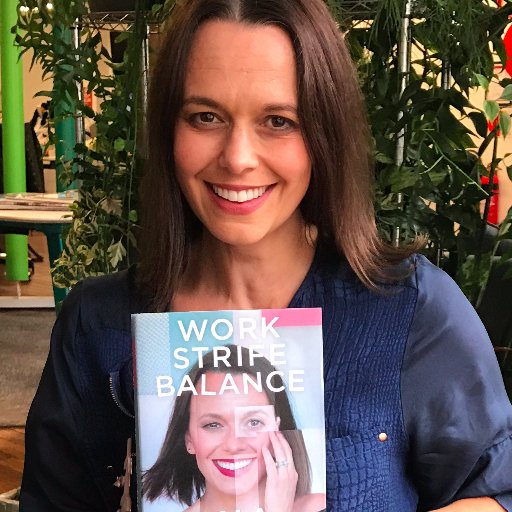

In this episode, I speak to Mia Freedman, journalist, author, founder of lifestyle website Mamamia. Mia is no stranger to stress. She wants a successful business with more than a hundred employees. She host her own podcast and she's married with three kids. But Mia has also written very honestly about her experience with generalised anxiety disorder in her latest book: “Work, Strife, Balance.” It’s interesting to me particularly because I’m in my 70’s and in my book which was called “No job for a woman”, published by University of Queensland press, I talked about the stress and anxiety that I went through of course, as normal part of living but anxiety, in those days and I’m talking about you know, 14 years ago was never recognised as a mental disorder; and now it actually is. So, we talked about how she manages her anxiety when running a successful business and raising her children, and the research that QBI scientists are doing in an area of the brain called the amygdala, which is where anxiety disorders tend to develop.

So, how to introduce Mia Freedman? Well, she is so many things as I’ve already said. She's the co-founder, the creative director of the Mamamia Women's Network which is Australia's largest digital media company. MWN began as a personal blog in Mia’s lounge room in 2007, but now it reaches 4 million women per month, with offices in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, and New York. And in addition to the website's Mamamia and Spring street, MWN also has the women’s largest podcast network with HO's reaching millions of women. So, I think it's fair to say that Mia Freedman, is a woman of enormous influence. She's also the author of three books. She's formerly a magazine editor and a newspaper columnist. She was named as one of Australia's hundred most influential women by the Financial Review and as a former chair of the Federal Government’s Body Image Advisory Board. She's been a passionate campaigner for more diversity in the way the media portrays women and with all of that she has three children, two dogs and she runs MWN with her husband, who I think very importantly is the CEO. Well, Mia how are you?

Mia: I’m exhausted after hearing all that, Sallyanne.

Sallyanne: So am I. I’m exhausted, too but anyhow, I pick myself up from the floor where I have lain exhausted and just talk to you about stress and anxiety and all that sort of thing because in your new book “Work, Strife, Balance”, you write very openly about your own struggle with anxiety. So, when did you first realise that you had anxiety? Did you recognise what was happening at that time?

Mia: No, I don’t think I did, until I sort of, it reached the critical point. I suppose, a little bit, like what you said, that I was aware of depression. No, I was familiar with depression and I hadn’t really experienced that, but I wasn’t… there was a lot less understanding of anxiety until I think recent years. And so, I didn’t have a name for how I actually felt, or how felt on and off through most of my life, until it got to critical point. I was diagnosed. I started taking medication and it went away and it was only the absence of something that made me see how evasive that had been through my life, if that makes sense. But it all came to a head about probably about five years ago, where I had an episode of anxiety that was really quite intense. It lasted about 10 or 11 days and it was triggered by a really funny thing, in that I went to a health retreat and I dismantled all the things that I had inadvertently or subconsciously, I suppose, done to manage my anxiety and then it took away all my crutches. It took away being busy. It took away stimulation. It took away my routine, in many ways. It took away even silly things, like cups of tea. And when I was actually at the retreat it was fine because they keep you really busy at least twice and you’re doing this; and doing that and you gone on a walk; and you’re doing Tai Chi, and you’re going to a lecture and you’re having a massage; but then when I left the retreat after about five or six days I decided – because it was Christmas – I decided to try to carry on some of those things into my life. And then, this also sounds ridiculous, but my computer broke and so, suddenly I was very unmoored and unconnected from the world. You know, this was before smart phones were a huge thing, and before, I suppose, I did as much on my smartphone. Now it wouldn’t be as much of a crisis because I still have my smartphone to occupy me. So, I was on holidays and I had this anxiety attack that was triggered by a little twinge in my side which I immediately self-diagnosed as being ovarian cancer. And it sounds so ridiculous now, in hindsight…

Sallyanne: No it doesn't sound a bit ridiculous. [Chuckling]…

Mia: … And it wasn’t until much later, or a number of weeks later, that I was diagnosed with something called somatism which is anxiety were you… it’s also sometimes called health anxiety, but it's basically where you manifest physical symptoms based on a condition that doesn't exist but that it sends you into a spiral of anxiety. And it really didn’t let up for about 10 or 11 days and after that point, I went and saw my regular therapist. I’m a strong believer in therapy and have seen therapist on and off through different periods in my life and she was the one that said, “I think you've had a nervous breakdown and I think you know it's time to go and see someone and look at medication”.

Sallyanne: And you did.

Mia: And I did, I saw a fantastic psychiatrist a lovely man called, Dr. Ben Teoh and he listened to my story and he said you know, “I think you've got generalised anxiety disorder”, and he explained to me what that was and how it manifests. And he explained it to me in terms that made a lot of sense. He said that you know, if you think about it as a sort of a chemical malfunction in the brain, he said some people… a person without anxiety disorder would walk down the street and if they heard footsteps behind them in the dark street, their body releases or their brain releases adrenaline, which is part of fight or flight because they might have to flee danger, but then as those footsteps passed and the brain realised you actually weren't in danger, that release of adrenaline would be stopped and you would feel fine. But, when you have a condition like mine, you can be sitting at home in your lounge room having a cup of tea but your brain is releasing adrenaline and responds as if you we're being chased around your house by someone wielding a knife - even though there is no physical danger and there is no actual,even ephemeral, danger. But you feel constantly this feeling of dread or this feeling of panic.

Sallyanne: We're going to talk in a minute, or I’m going to talk in a minute about the research that QBI is doing on the brain and that part of the brain that really makes those things happen, but I’m just interested you know, you've got so much going on in your life. You're a successful business woman. You've got three children. You've just written this book and you probably thinking about the next book. You're dealing with a husband. I imagine that your daily life in the ordinary day to day sense is pretty frenetic, involves sort of juggling. How do you distinguish between ordinary stress and your anxiety? Because I think this is really important for people: I’m stressed, I’m feeling anxious, is this ok? Is this normal? When does it become abnormal? You've described how it became… how you realised that you had something that was beyond normal and you did something about it, but how do people actually say well, is this the normal stress? I mean as I remember you know when I was young and I’d say to mother, " Oh, I'm feeling stressed" and, she'd say; “Yes, yes, you know you're doing too much. Stop doing it! Get over it!” But, now of course, thank goodness we're realising that there is a mental condition involved.

Mia: It's such a good question Sallyanne and I'm often asked that because stress I’m fine with; in fact, stress like I quite enjoy and stress is actually something that's probably almost impossible unless you moved to a yurt in Mongolia is impossible to… impossible to eliminate from your life altogether. Particularly if you’re a woman. Particularly if you're a woman who works and has children. But anxiety is different. So, as you say I'm often very busy. I can often be a very stressed. I get up and I have to speak in front of a thousand people. I might have to go on live television. I might have to be sitting here during this live podcast interview here. Now, I no longer feel stressed. I no longer actually feel stressed and I certainly don't feel anxious about any of those things. I think for me understanding anxiety was when part of it to me was catastrophising, was believing a terrible thing was going to happen, or a terrible thing had already happened in terms of ‘I have a ovarian cancer’ when in fact, I didn't. So, I suppose for me anxiety is often something that you can't even attach to something. It's just almost an existential feeling of dread or fear. Now, anxiety can often attach self to things. So, for a long time I was terrified of flying. After I had children I became terrified of flying. It can attach itself to different people, you know, driving or being in tunnels and some people have panic attacks. For me, it wasn't that. It was generalised anxiety. And it was just this feeling that I would wake up within the morning and it wasn't attached to anything I couldn't… it's not that I was nervous about a big thing that was happening at work, wasn't that I was worried about my kids. I mean all of those things were humming in the background but it was a very I don’t know what you'd say. There are aspects of stress that can be productive, like it's normal to feel stressed if you've got to do an interview or give a speech, or you're getting married, or you've had something happen in your life, a bad diagnosis or something. Stress is normal and stress is a normal response to things that go on in our lives but anxiety, is it almost doesn’t fit. And I suppose that’s when I became aware of the difference and I know to this day the difference. I can feel stress. I can feel overwhelmed very easily but anxiety is different. Anxiety is just, it’s just a kind… it’s like this feeling of dread that's all I can explain… the best way I can explain it.

Sallyanne: I think that’s a good explanation because stress by itself is productive. It’s what fires us up to do certain things. It’s a bit like I’ve always thought the difference between depression and grief. Grief is when there is something real for you to be sorrow grieving about; depression is when you don’t know why you're sad and it’s that whole feeling it just being miserable, but there's no actual cause for it which is very worrying. Something else I did want to ask you is what you find helps your anxiety? I mean obviously, medication but do you meditate? Do you dream about special places? What are the tools?

Mia: Well, that’s another great question. Something I realised, since been diagnosed, is that a lot of my life I have set up subconsciously to manage my anxiety. So, there are few things. Routine, is crucial for me. I like to do the same thing every day. I like to eat the same foods certainly, for breakfast and lunch every day. I have certain things that I do… not in a OCD way, but just I like familiarity. You know, when I travel, I carry… I travel with a certain teacup that I would just really like because I like big cups of tea when you’re staying in hotels, they give you little cups of tea. So, little things like that. Exercise everyday which I used to think was connected to body images that issues and I had an eating disorder when I was much, much younger and I thought that it was a hangover from that – perhaps, in part it is – but I've since realised that exercise is really a crucial tool in managing both anxiety and depression. So, that's non-negotiable for me. And sleep. Getting a lot of sleep is really important. And the fourth pillar for me is being busy. Having a project. Having something to do. And I kind of liken it to being a cattle dog and if that cattle dog doesn't have sheep to round up, it's going to dig up the garden. And, that's a little bit like my mind. So, this idea of you know being present and not looking at your phone and that's fine in moderation but for me completely detaching is not healthy, because when I try to do that, for example on holidays. One of the reasons I realised I've always resisted the idea of holidays – my whole life and I come home early from almost every holiday I've been on – is because firstly, it’s disruption to my routine. But secondly, I like to be busy. So, now I don’t try to completely disconnect from work when I’m on holidays, or else I have to replace work with something else like diving into a book and consuming myself with that. I always need a project and a lot of it I think is just accepting your eccentricities or your quirks as actually being ways to self soothe and treat anxiety.

Sallyanne: I think it’s called self-awareness or having insight.

Mia: Yes

Sallyanne: I think it's really important and that of course is the benefits of talking to somebody like a psychiatrist because they can actually say you’re this kind of person and that's important. One of the thing, I'm just going to talk to you, Mia, a little bit about the kind of research that we're doing it at QBI because I think it's so exciting of course we all know how important the brain is. The brain is the most important organ in your body. It really, pretty much, determines the functions of absolutely everything else. So, at QBI, we – or I should say they because I’m not actually doing those research – do research into a hall host of things. You mentioned anorexia that’s something we're… we’ve got a unit at the science of learning. How kids… how they learn not so much what they learn. We talked about you know dementia and successful aging, which of course is something for you to look forward to, my dear.

But anxiety, I think it’s fantastic that anxiety is now being recognised as a proper, if not a disease certainly, a disorder but something bad is deserving of medical attention and research attention, so you've written in your book about having a heightened fight or flight response in anxiety, but what we know now and what they're doing they research on at QBI St. Lucia, is the small region of the brain called the amygdala. I'm going to talk a little bit about the amygdala because it's very important for fear conditioning which is when you associate something, an incident or an object with something fearful. So, for example if you get bitten by a dog when you we're a little girl you might then go through all your life being scared of all dogs no matter how cute or gentle they are. Fear conditioning is actually a good thing because it gives you that classic flight-or-fight response. Your heart beats faster, your blood pressure increases, your mouth gets dry and that was very useful a long time ago when we were being chased by dinosaurs or whatever. In humans the amygdala, also gives us cognitive effects like the feelings of dread and despair that Mia's described. Anxiety disorder has now been linked to disrupted connections in the amygdala which affects how it processes fear and anxiety. So, this tiny almond-shaped region of the brain is related to anxiety and to post traumatic stress disorder and it's very important. Using electrical recordings, imaging and experiments, QBI researchers have identified some of the key brain circuits involved in anxiety disorders.

Our Director Professor Pankaj Sah’s lab studies the connections in the amygdala. They’ve discovered the molecules that make up brain receptors in the amygdala which are potential targets for new anxiety treatment drugs. So, that's just a small capsule of what actually is happening out there and I think why the work of QBI is important and we are so grateful, Mia that you’re coming on and letting us talk about it and letting people out there know that work has been done on a whole host of disorders that perhaps people in the past put up with and the fact that you have come out and talked about it is really very important and we certainly thank you for doing that.

Mia: Oh, it’s my pleasure. It’s one of those things that I wish that I had known more about it when it happened to me and I think that it’s like so many things in life there are these all these secret clubs that you don’t know exists until you inadvertently join one. And then when you start mentioning it and when I started confessing I suppose or confiding, might be a better word, in some of the people around me it was like "Oh yes I've got anxiety and I take medication. Here's how I handle it", and suddenly I realised there’s this huge community of people who were struggling and suffering, often silently, with what's a really, really common, you know, mental health issue.

Sallyanne: And, just one just last question before I let you go and I thank you for giving us all your time...

Mia: Oh, my pleasure!

Sallyanne: …Just how do you describe an anxiety attack? What does an anxiety attack feel like? You said it's when you wake up in the morning and you have that feeling of dread and is probably something that during the day you suddenly think "Oh my God! I definitely got cancer; or there’s a man about to murder me; or the sky is going to crash into me’. But can you just describe, what does an anxiety attack feel like? It comes on suddenly?

Mia: Well, I’ve only ever had you know, I suppose I describe it as an attacker I’m not one that gets panic attacks. This is what happened to me at that time in Christmas. It was like a prolonged period of anxiety. For me, the experience that anxiety is a combination of panic and resigned dread. So, panic often… the word panic kind of denotes a frenzy of activity. There's something about anxiety that can be very, very deadening because it's almost a certainty. It’s a fear but it’s a certainty, as well. That something bad will happen. So, for example when I used to have anxiety around flying I would be so… my body and my brain would react as though the plane had already crashed and I would be so shocked when it landed. I would be surprised and delighted.

Sallyanne: Somebody would have said to you as you're getting on that plane "No, this plane is not going to crash. I've flown millions of times before. The pilot is fantastic", but you would still feel anxious about it.

Mia: Because it's illogical. It’s completely logical you know, I had to complete certainty that I had ovarian cancer despite not having a single test, not having a scan. My mind was sort of went forward to the point where it was all confirmed and I couldn't even… The other thing that could be really isolating is that I couldn’t even express it to my husband because that would somehow make it real. And so people would say, you know and I know other people with somatism as well, who they go "If you’re worried that you’ve got some type of cancer or some type then just go and have a test" and I would be like "I’m too scared to have the test", and you know when I was younger I realised now that I had a period where I was convinced I had HIV. Convinced and I was way too scared to have the test and I don’t think I would’ve have the test but my doctor when I fell pregnant sort of one of the routine test was HIV and I think he sort of tested me without me even realising it and, that was always something at the back of my mind. So, none of it is logical. None of it is logical. None of it is rational. And I now find also its very helpful if I’m… because sometimes I still get anxiety – it’s just important to say that – it’s rare thanks to Lexapro and everything else I do to manage it. But sometimes it still happens and if I say to my husband, I’m just having a bad day or I’ve got really bad anxiety at the moment that helps enormously and I can’t even tell you why. But just saying it out loud somehow makes it less overwhelming that feeling and less lonely because anxiety is a terribly lonely feeling.

Sallyanne: Well, it’s deep within you. So, sharing it with somebody just sort of brings it to the surface a little bit, doesn’t it?

Mia: Yeah, it really does and the monster is less scary when you say it out loud. It just is

Sallyanne: Well, Mia thank you very much indeed. We're going to keep you in touch with what we're doing when they find some sort of breakthrough and more information. We're going to let you know. You'll be the first

Mia: Thanks so much and it was so lovely talking to you.

Sallyanne: That was Mia Freedman, talking about her anxiety. That's all for this episode. I’m Sallyanne Atkinson. Our podcast was produced by Donna Lu and Jessica McGaw. If you enjoyed this episode, do tell your friends about it, give us a review in ITunes, or let us know what you think on Facebook or Twitter. Thanks for listening and there will be lots more to come.