Dementia risk factors

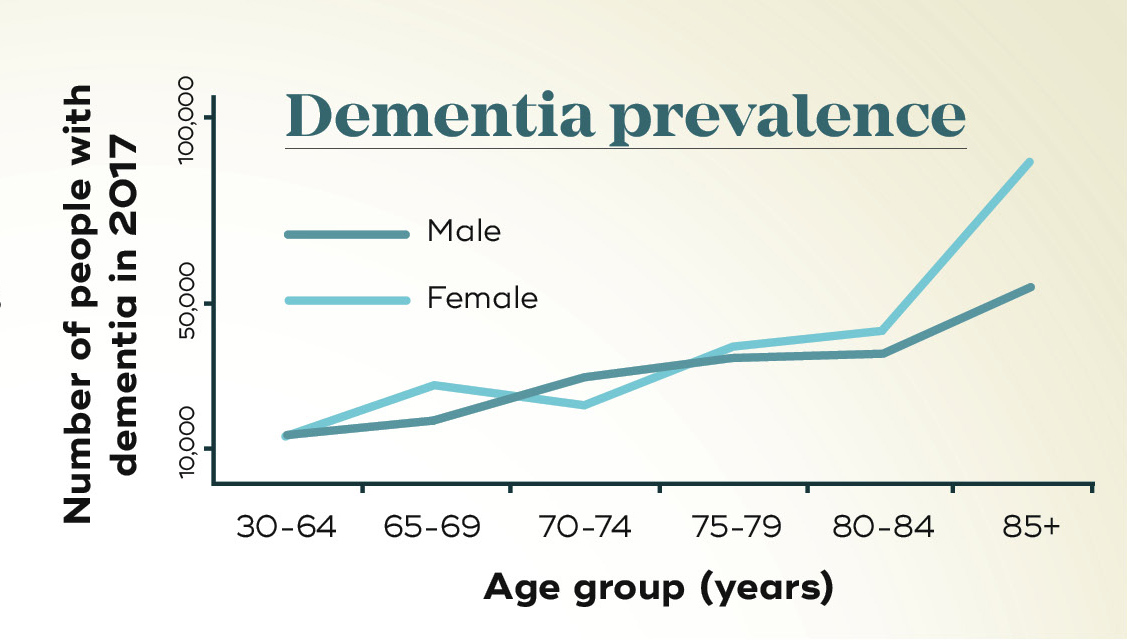

Age: the biggest risk for dementia

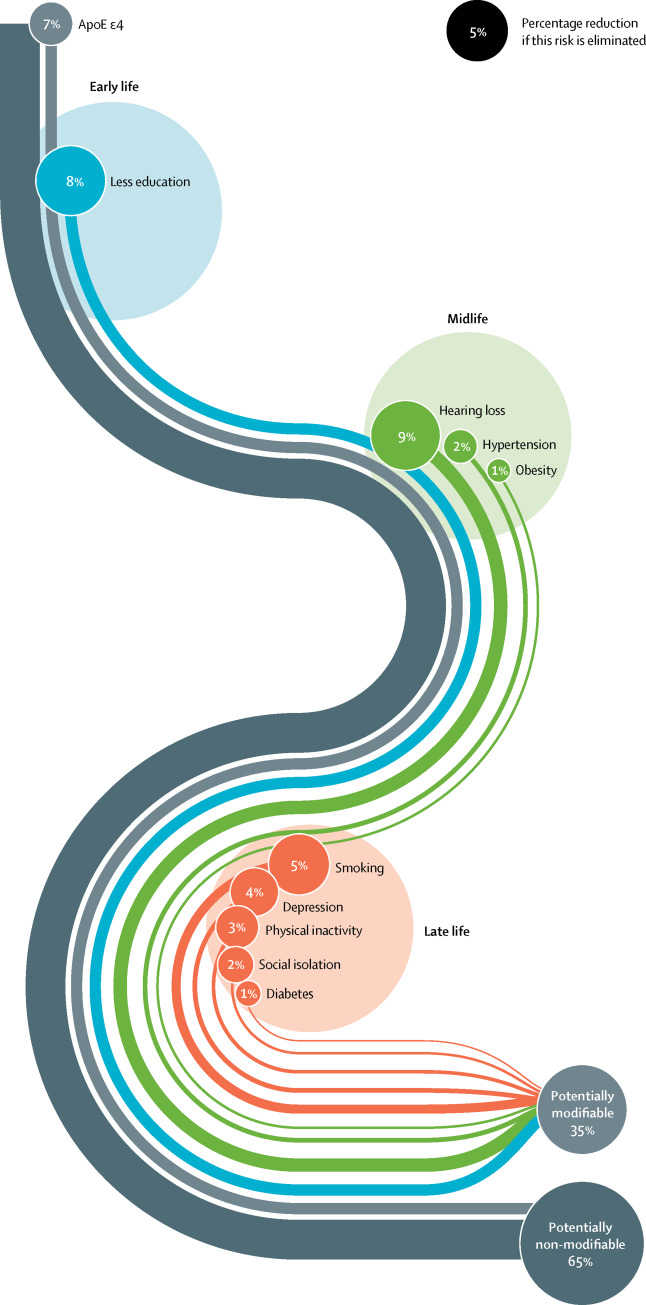

Age is the greatest risk factor for developing dementia. As with our genes, we unfortunately can’t do anything to overcome ageing! However, there are environmental factors that seem to influence the likelihood of dementia and could account for about one-third of the overall risk of developing dementia. There is some evidence to suggest we can take steps to lessen the impact of these factors.

Cardiovascular health

This has one of the strongest links to dementia, particularly Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. High blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, diabetes, stroke and heart disease all increase the risk. The connection seems easy to understand – our circulation supplies vital nutrients for the brain, and if something interferes with that, our neurons will suffer. In reality, we're still trying to figure out how these changes might cause build-up of toxic aggregates.

Lifestyle choices

Smoking, drinking, inactivity, and limited social and mental stimulation may increase the risk of dementia. Some of these may be linked to poor cardiovascular health, and methods to increase physical activity in older patients are being investigated to see if they can delay dementia.

Modifiable risk factors

- Smoking

- Chronic alcohol use

- Lower education level

- Physical inactivity

- Social isolation

- Chronic sleep deprivation

- Poor diet

- Diabetes

- Heart disease

- Hypertension

- High cholesterol

- Head injury

- Hearing loss

- Obesity

- Depression

Head injuries

There is now evidence that head injuries – even mild, repeated concussions – can be associated with the development in later life of a kind of degenerative disease called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). One recent study reported that an incredible 110 out of 111 former NFL (American National Football League) players, whose brains were donated to researchers, showed signs of CTE. This disorder has many of the same physiological hallmarks of forms of dementia, particularly the abnormal deposits in the brain of the proteins tau and TDP-43.

Sleep disturbances

People with dementia commonly have sleep disturbances, even years prior to experiencing symptoms. As with many risk factors, whether this is a cause or a symptom of dementia is unknown – and it’s likely to be both. Alzheimer’s disease is known to alter production of the hormone melatonin by damaging a part of the brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus, which is responsible for regulating our circadian rhythm, or the sleep/wake cycle. As a result, people with dementia may find it harder to go to sleep and stay asleep; they may sleep for just a few minutes and think they have slept for hours.

Sleep also helps to consolidate memories, and a lack of sleep, or the right kind of sleep, can impact memory recall. A recent study linked one night of sleep deprivation (of slow-wave, or deep sleep) to increased levels of amyloid-ß, the main compound in plaques that hasten neuron death. Chronic sleep deprivation was also linked to an increase in tau, a key protein that forms tangles inside neurons, leading to their death.

One of the most common reasons for sleep disruption is sleep apnoea – when upper airways collapse during sleep, resulting in sporadic pauses in breathing that require the person to momentarily wake up to breathe.

People who suffer from sleep apnoea are two to three times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease, says Professor Elizabeth Coulson, from the Queensland Brain Institute and the School of Biomedical Sciences at UQ.

“This could be because hypoxia – lower levels of oxygen in the blood from poor breathing – causes nerve cell death,” she says. Find out more about Prof Coulsen's upcoming sleep apnoea study.

Modifiable risk factors for dementia