How is dementia diagnosed?

When signs of cognitive decline and changes in personality or social behaviour can no longer be ignored, a GP visit is often the next step. The doctor will take a patient’s history, assess their physical and mental abilities, order investigations and, if necessary, refer to a specialist geriatrician, neurologist or psychiatrist. Standardised cognitive tests are used by both GPs and other specialists. Examples are the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the clock-drawing test. Some states also have early memory assessment clinics.

The vital role of the GP in dementia

General practitioners (GPs) are involved in the care of a majority of people with dementia, from first diagnosis and care at home, through to visiting them in residential care. The GP’s role at first presentation is to rule out all other causes for cognitive changes. GPs also rely on aged care assessment teams (ACATs) at their local hospital or community health centre, and support and information from Alzheimer’s Australia.

Looking after the carer's emotional and physical health is also crucial. The GP may organise respite care, community nursing or support the transition to residential care. For families, the psychological and behavioural symptoms of dementia are often more distressing than the memory loss, and care is typically time-consuming and exhausting.

Doctors have a duty to remind patients and carers about legal and planning issues, such as setting up an enduring guardianship or power of attorney, and an advance care directive, early in the illness.

Brain scans

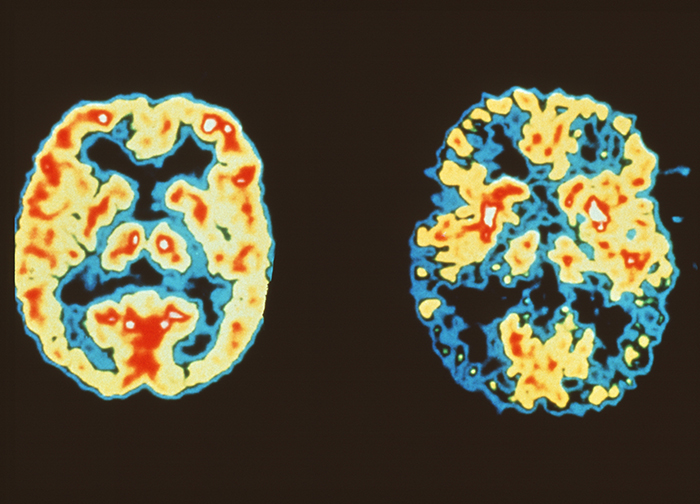

Imaging technologies such as CT or MRI, which reveal the structure of the brain, can detect changes in the features of vascular dementia, and the shrinkage of brain tissue caused by degeneration. Other types of scans, such as PET, fMRI (functional MRI) and SPECT, show localised changes in brain activity and can be used together with cognitive and behavioural symptoms to aid diagnosis. A new imaging method called PiB-PET is being investigated for use in showing amyloid-ß plaques.

An abnormal scan alone, however, is not a diagnosis. It is important to note that imaging tests can fail to detect abnormalities, especially in a person with early dementia, and scans can be lengthy, unpleasant and expensive. Currently, scans are mostly research tools and not used for diagnosis and management in the general community.

Biomarkers for Alzheimer's plaques

Other research is looking at whether lab tests of biomarkers, such as the level of amyloid-ß and tau in blood or cerebrospinal fluid, can predict a susceptibility to dementia. However, the work is complicated by the fact that different forms of amyloid-ß and tau exist. The key is to correctly identify the toxic forms.

Finding biomarkers of dementia will be critical in early diagnosis and treatment. One large-scale study looking to do this is the Australian Imaging, Biomarker & Lifestyle Flagship Study of Ageing (AIBL), a longitudinal study aimed at determining what biomarkers, lifestyle choices and cognitive abilities best predict the development of Alzheimer’s disease.