When you look at the world, your brain doesn’t just react to what it sees; it also expects certain things to happen next. Our brain constantly makes predictions based on experience, a process called predictive coding, which helps it process information faster and more efficiently.

In the Mattingley lab at UQ’s Queensland Brain Institute, researchers are studying how the brain combines different types of predictions about what we will see (such as an object’s identity) and where we will see it (the object’s location) to understand how these expectations affect brain activity.

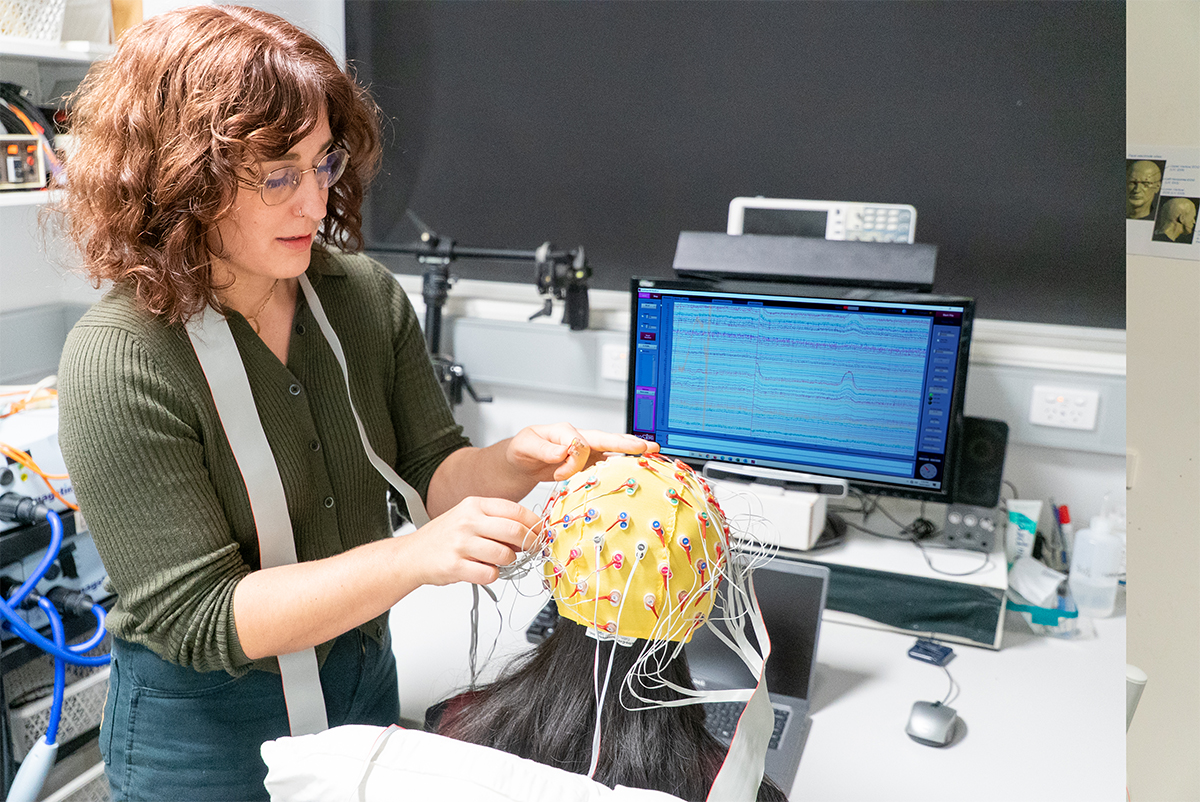

Dr Margaret Moore is leading this research. She explains how the team investigated brain activity by showing 40 people a fast stream of pictures of real-world objects.

“While participants viewed the images, we recorded their brain activity using an electroencephalogram (EEG). This is a non-invasive tool that measures electrical signals from the brain and can distinguish distinct activity patterns that are just a few milliseconds apart,” Dr Moore said.

“Sometimes, the order or location of the objects was predictable, and sometimes it was random or unexpected.

“We do this by first creating patterns in which some objects predict what the next image will be, and then layering this structure onto a separate pattern which predicts where the next object will appear.

“This allows us to directly compare how the brain responds to the same objects and locations in cases where this information is in line with the patterns (expected), violates the patterns (unexpected), or is completely unpredictable (random).”

How predictions of object location affect brain activity

The researchers found that when the location of an image was expected, the brain initially showed only weak activity patterns, but then a fraction of a second later these patterns strengthened.

Dr Moore explained when you see an object in the world, neural activity goes through various stages, from basic processing of simple features like shape and colour, all the way through to recognition of the object as something familiar.

“For example, if you were looking at a duck, initial processing in the brain would extract the basic shape and colour information,” Dr Moore said.

“In later stages, this information is passed on to brain areas that store all your knowledge of real-world objects. In an instant, you know you’re looking at a duck.”

“Our study shows that the brain first uses its prediction to simplify processing, and then later refines its understanding.”

Predictions about what object an object is

“The time-based pattern didn’t happen in the same way for predictions about what object would appear,” Dr Moore said.

“When an image was unexpected, the brain’s ability to represent it clearly was reduced in later stages of processing.

“This tells us that when something is surprising, we might not have as much information about it.

“Overall, these results show that the brain’s predictions make processing faster, but significantly, they change over time and depend on what kind of information (what vs where) the brain is predicting.

“This study expands our understanding of how the brain balances efficiency and accuracy when making sense of the world.”

The team is planning a follow-up study aiming to measure how different types of predictive information interact.

This research was published in Imaging Neuroscience.