It’s the dead of night. She grits her teeth and holds back the cries of pain – the noise could alert the men fighting around her. She summons the strength for one final push and welcomes into the world a baby daughter. There are no embraces, no words of joy – time is not on her side. She’s racing to save the lives of her young family.

This is how Queensland Brain Institute (QBI) researcher Nyakuoy Yak started life – born on a desperate escape from the brutal civil war ravaging her birthland of Sudan.

Caught between two conflict zones, she was born in what is now the Abyei Area, a joint sovereignty zone between Sudan and South Sudan formed at the resolution of the Sudanese Civil War (2011).

“The story of my birth is rather dramatic,” Nyakuoy said.

“My mother was travelling with a few of my uncles to a UN pick-up location to go to Khartoum where my grandparents lived.

“There was fighting all around and how she managed to give birth without giving away their location I’ll never understand.”

Whisked away by helicopter, Nyakouy and her family had taken the brave, yet terrifying, step into an uncertain future.

It’s a future shared by more than 2 million refugees who’ve fled the violence in Sudan.

Maths, science help young refugee

Nyakuoy sits behind a microscope, her eyes brush against the lenses, while her fingers lightly twist the focus. She smiles as the cells appear on the plate, watching as the cellular world comes alive.

“Microscopes are what I love the most,” Nyakuoy said. “I think they are a wonderful tool to streamline the scientific process and visualise how cells behave and interact with each other.

“People underestimate the types of questions you can ask with a microscope.”

Nyakuoy completed her Bachelor of Science at The University of Queensland (UQ) in 2018, majoring in Microbiology, Biochemistry and Cell Biology, before doing her masters with Professor Jennifer Stow at the Institute for Molecular Bioscience (IMB).

“I struggled a lot in primary school because I didn’t understand English very well, and a later diagnosis of Asperger's Syndrome (autism spectrum disorder) complicated things further” Nyakuoy said.

“But it helped me pick up the patterns in maths and follow the science demonstrations, so maths and science became a huge part of my life growing up.”

Under the guidance of Professor Stow, Nyakuoy, with the help of the dedicated team of microscopist at the Microscopy Facility at IMB, started to appreciate the power of microscopy and cell biology.

But despite having access to some of the “best microscopes in the world” a new idea was looming, and with it, a new career path began to grow, one which led to QBI and the lab of Professor Frederic Meunier.

From refugee camp to Toowoomba

Refugee camps are a sprawling mass of people. They are overcrowded and largely under-resourced. Fear, anxiety and desperation flitter from face to face.

A young Nyakuoy also called them home.

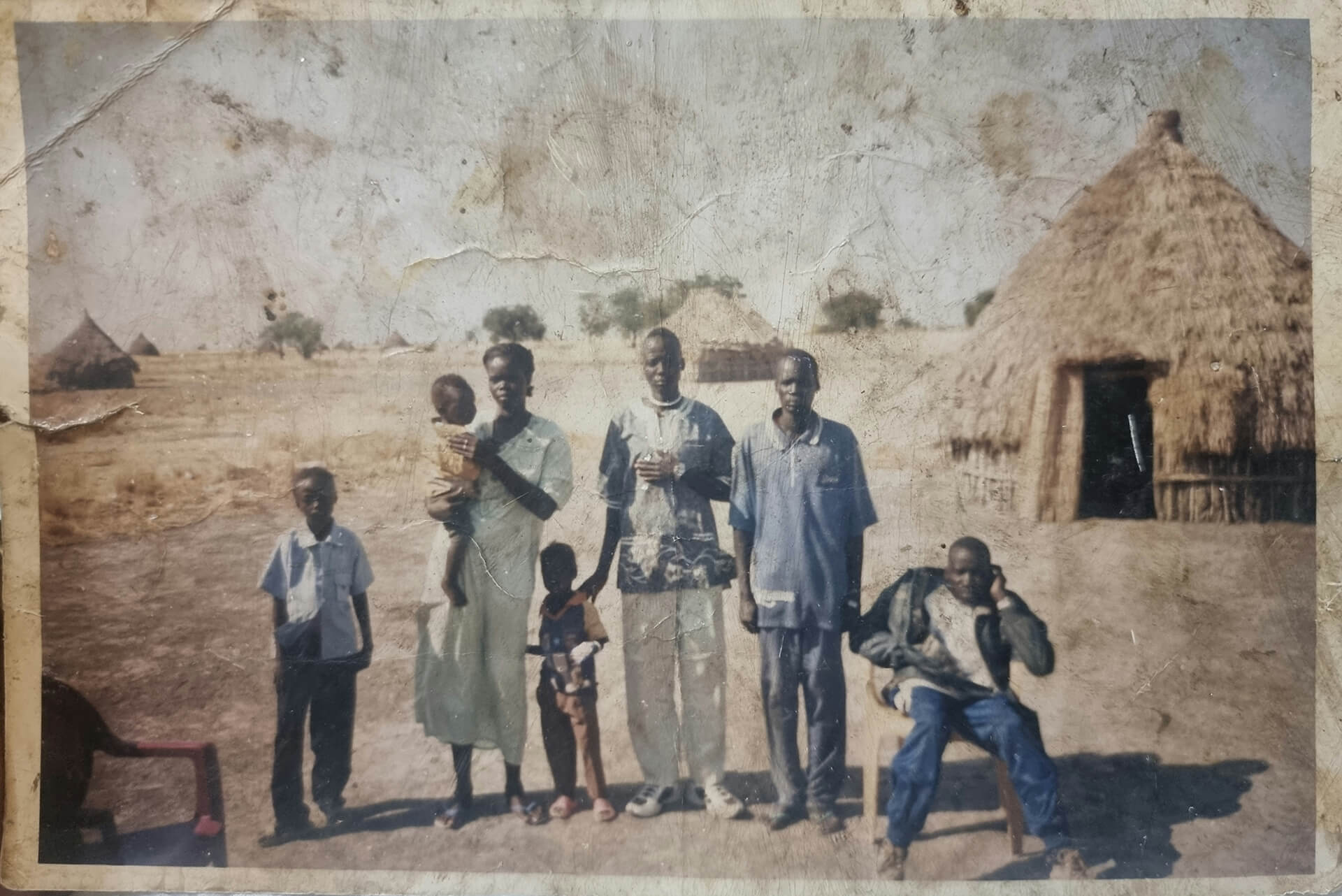

Airlifted to safety following her birth, Nyakuoy and her family – soon expanded with the birth of her sister– were moved to one close to Khartoum, the capital of Sudan.

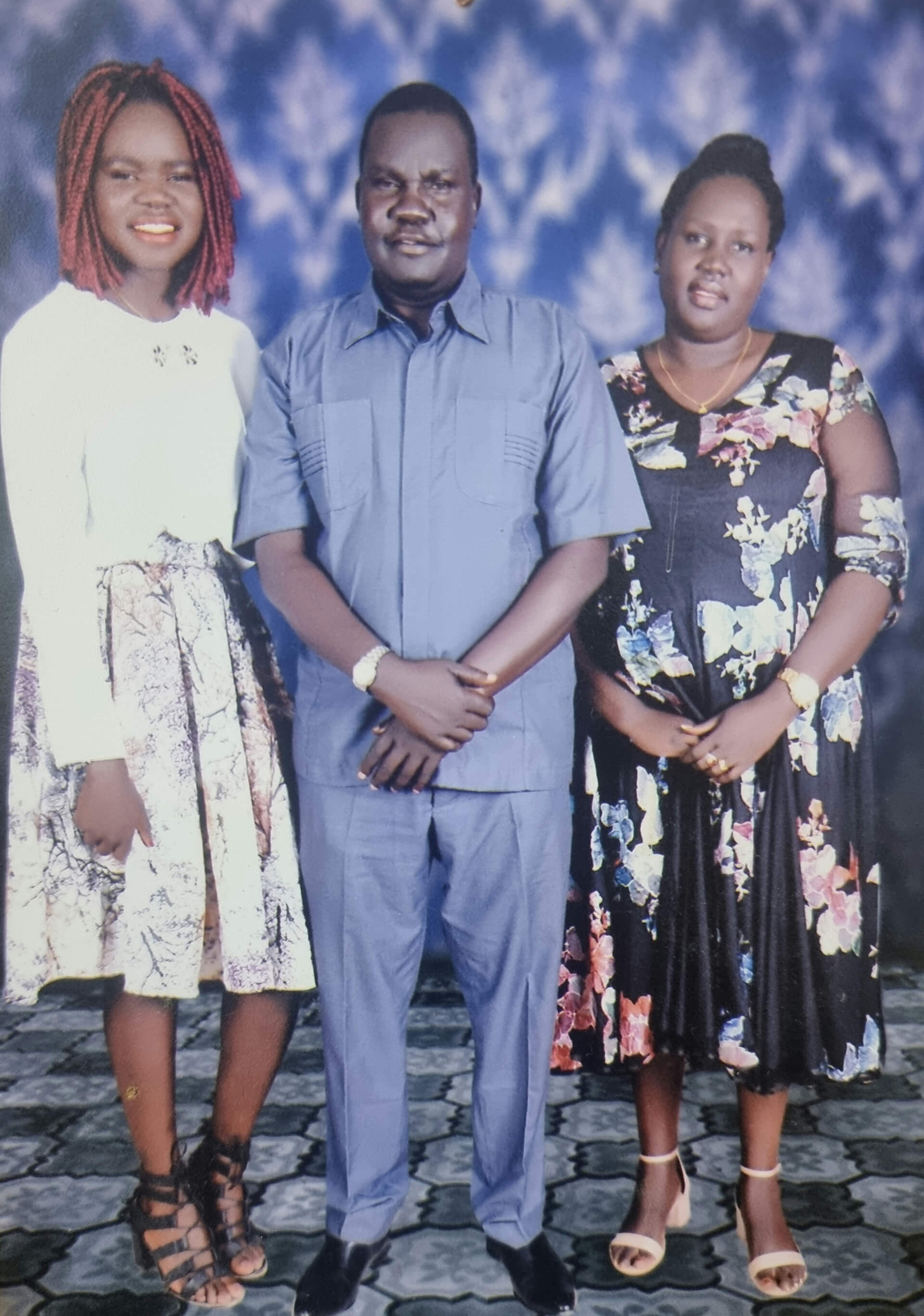

The family then travelled across the Kenyan border to live in a refugee camp in Nairobi, where her youngest sister was born. However, her father remained in Sudan to continue his work as Sudanese Commissioner. James was later appointed Deputy Inspector General of the newly formed South Sudan Police, a role he continues to do away from his family in Australia.

Nyakuoy’s mother was determined to provide a better life for her children, and for several years, applied, re-applied, and re-applied again, for refugee status in Australia.

Nyakuoy was ready to celebrate her eighth birthday when she set foot in Toowoomba in 2005.

Different people. Different language. Different world.

“We struggled a lot,” Nyakuoy said. “We had a really hard time with things people don’t realise you have to adjust to.

“The first time we went grocery shopping, we all got dressed up, mum walked us over because we didn’t have a car, and we had no idea how to get anything.

“Mum just chose the first white mum she could see and we followed her around and picked up everything she picked up.

“Our lunches were very bizarre in the beginning, like a can of beetroots, a whole cucumber or vegemite and honey sandwiches.

“Mum was alone with no English, and four small kids – I don’t know how she did it. She’s amazing!”

Passion for microscopes reveals new dream

The microscopy team sit in an office on the fifth level at QBI – almost directly adjacent to Professor Meunier’s office.

It’s a convenient location for Nyakuoy.

“I’ll just wander up to see Frederic and then just knock on the door of the microscopy room,” Nyakuoy laughed.

“I’m just going to bother them as much as possible.”

Nyakuoy decided to undertake her PhD in Professor Meunier’s lab to specifically learn about super resolution microscopy – a technique the team use to make new discoveries about the brain.

It was a decision she made after successfully applying for the Westpac Scholars Future Leaders Scholarship – a program which invests in the next generation of pioneering Australians. It will help Nyakuoy with her studies and take her across the world to visit leading research institutes.

It will also help in her aspirations to become what could be an Australian-first: a local microscope production company.

“Australia doesn’t really have a microscopy manufacturing company,” Nyakuoy said.

“All of our research microscopes are imported from overseas.

“So I would love to do something where I can build microscopes and then commercialise them here in Australia.”

A hard start to a new world, new life

The tears started first. Then the mournful howl. Then the begging.

Nyakuoy did not want to go to school. Not without her brother.

The grade three Harristown student did not, could not, face a day of being the only African student in a primary school in rural Queensland.

“No one looked like me,” Nyakuoy said. “All of these kids were so incredibly white.

“My brother is a year older than me, so he should have been in year four, but I didn’t understand what anyone was saying, or doing, and I couldn’t be alone in this.

“We sat together and tried to figure out what the teacher was saying, because there were no translators, there was nothing, it was just me and him trying to figure out what everyone else was saying.”

The disconnect between Nyakuoy and this new world invaded all aspects of life.

“We moved into social housing when we arrived and it came with a television,” Nyakuoy said. “We’d never seen a television before!

“We managed to turn it on, but for a year, didn’t know how to change the channel.

“We were watching shows like NCIS and The Simpsons without a clue of what was being said.”

But, slowly, support started to arrive.

First, there was a Toowoomba couple, Neil and Wendy Peach, who still play major roles in Nyakuoy’s life, then the local church, and, as more refugees arrived in Australia, a growing Sudanese community.

The family began to learn English, Nyakuoy’s mother passed her driver’s licence and completed a Certificate III in Age Care/Home and Community Care and in grade 10, Nyakuoy was awarded the UQ Young Achiever Scholarship.

Past, present merge to create conflicts

Nyakuoy’s first year at university was tough.

She struggled to adapt away from her family, focus on her studies and keep her head above water. What little money she had after paying rent and bills was sent home, and to family in Sudan.

Family secrets, long thought buried, began to peek through the cracks.

Old feuds, never forgiven or forgotten, which violently splintered her birthplace during the war, now splintered friendships and communities.

And the threat of expulsion loomed eternally on the horizon.

“I was living on a packet of noodles every four days,” Nyakuoy said. “I wasn’t sleeping, it was hard to concentrate.

“Financially, physically and mentally, I struggled quite a lot.”

Nyakuoy said she’s still dealing with the childhood trauma and the impact from that first year and continues to seek professional help for both her mental and physical wellbeing.

But Nyakuoy – born on the run, raised in refugee camps, and who discovered a saviour in science amidst a foreign language in a foreign land – found the way to re-build her confidence.

And now, on World Refugee Day, Nyakuoy looks over her shoulder to stare down the road she has taken, knowing it’s a road shared with refugees who are still trying to find a way home.

“World Refugee Day is a day for me to reflect on my family’s journey, and celebrate the resilience of past, present and future refugees as they flee their homes in the hopes of a better future,” Nyakuoy said.

World Refugee Day is an international day designated by the United Nations to honour refugees around the globe. It falls each year on June 20.

If you need to talk to someone about your mental health, please contact Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636.