Life as a carer: Robyn Hilton's personal story

Living with and caring for someone with dementia is challenging, heartbreaking, and exhausting; so many questions arise to which there are few answers. It’s a disease that continues to confound medical and scientific experts. Medication is available that will temporarily slow the progress of the disease, but there’s no cure.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia; and today, 425,000 Australians are living with dementia, and 1.2 million Australians are involved in their care.

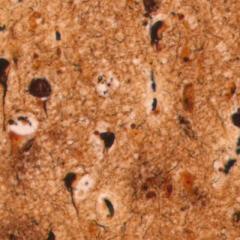

Although the causes of Alzheimer’s disease are not yet fully understood, its effect on the brain is clear – it damages and kills brain cells. And it doesn’t discriminate. It affects people from all walks of life.

My husband, Peter, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in February 2000 at the age of 66. The impact of that diagnosis was profound. Some time after the initial shock I felt pretty helpless because there’s no known cure, there’s no timetable for the inevitable decline, and there’s little effective medical treatment. Each case is unique, depending on the type of dementia, the personality of the sufferer, and which part of the brain is primarily affected. I likened it to feeling your way in the fog.

Thankfully, Peter’s decline was gradual. We loved travelling, so a few months after his diagnosis we spent 6 months driving around the United States and Canada. We travelled part of the Silk Road; we cruised the Danube and Volga Rivers; we went on safari in Africa; we regularly visited friends in the UK, US and New Zealand. Travelling stimulated Peter, and it was good. It’s important to try to maintain a sense of humour, and in this regard I recall, as we were sailing along the mighty Volga River, his commenting on how the creek he had spent so much time in and around as a child, had changed. I agreed that it was indeed a remarkable transformation of the creek where he learned to swim and where he and his father caught huge Murray River cod many decades before.

On one occasion in Africa Peter thought he’d been married off to a lovely lady selling beautifully painted fabrics on the side of the road. We had stopped to buy some fabric and, of course, got chatting to the ladies selling their wares. Peter always had a glint in his eye, and Anna saw it. She made it clear she liked Peter. It took some talking on my part to convince her that he was spoken for. He did have lovely blue eyes, and a cheeky smile, so I could well understand her attraction.

Inevitably, though, it became increasingly difficult, and then impossible, to undertake those trips.

More time was spent at home, but Peter wanted to be on the move. We would go for a drive, a picnic, shopping, and within ten minutes of coming home he’d want to be off again. At various times a carer would come and spend time with him and, hopefully, take him out. But he would refuse to go with anyone other than me. He was fully dependent on me and very unhappy if I left him in the care of anyone else for any length of time. He was my shadow.

One of the best things we did was to participate in the support groups offered by Alzheimer’s Australia (now Dementia Australia), at Woolloongabba. It’s important for people with dementia to maintain social interaction, and the support groups provided that opportunity. Just being in the company of people who are experiencing what you are, made the whole Alzheimer’s ‘thing’ bearable, or do-able. Each of us was at a different stage of dealing with the disease, so we were able to offer each other advice, friendship and laughter. Tears were shed, of course, but it’s the laughter that I remember so fondly. I always left our Thursday get-togethers feeling I could cope with, even conquer, anything.

Nine years after Peter’s diagnosis, he went into nursing home care. That was the most difficult and heartbreaking decision. The sense of guilt was overwhelming. It’s difficult to identify the ‘right’ time to do it. There are no rule books. It’s a very personal, and often lonely, decision. One matter I feel has to be addressed by government is establishing a staff to resident ratio in nursing homes. As you would expect, there is a staff to child ratio in child care centres. Why should it be any different for vulnerable elderly people in nursing homes?

Scientific research into dementia is being conducted in many universities and institutes around the world. The Queensland Brain Institute at the University of Queensland is a world leader in dementia research and recent discoveries have attracted international recognition. I think it is important for people with dementia, their families and carers, to know that they are not forgotten, and that there’s a lot of work going on behind the scenes to try to unravel the tangled web that is dementia.

Peter and I shared our lives with this wretched disease for more than eleven years, until he died seven years ago. It was a long and unpredictable road where underlying fear and great sorrow were ever present. That said, there were occasions which brought exquisite joy. You grasp those and hold them very close.

Note: In 2013, Robyn established the Peter Hilton Senior Research Fellowship in Ageing Dementia at UQ’s Queensland Brain Institute in Peter’s memory: https://qbi.uq.edu.au/article/2014/06/peter-hilton-fellow-appointed