This is your brain on Pokémon Go

Pokémon Go has taken the world by storm. (Image credit: WP:NFCC#4 / fair use)

If the viral response to Google’s 2014 April Fools’ video was anything to go by, the unprecedented success of Pokémon Go could have been expected. The game has been downloaded millions of times since its release on July 6, spurring meet-ups, making Nintendo’s share price soar and even prompting safety warnings. Players are obsessed: SimilarWeb reported on July 8 that users are spending an average of 43 minutes per day on the app—far surpassing time spent on social apps like Instagram and Snapchat.

Combining Google Maps and virtual reality, Pokémon Go uses real locations to encourage players to catch Pokémon with their phones. The further a player walks (or drives), the more Pokémon can be found. Using geolocation, a player’s smartphone vibrates when a Pokémon is in their vicinity—therein lies the key to its addictiveness.

Reward and addiction

Video games activate a specific network in the brain known as the brain reward system, which is responsible for desire, pleasure and positive reinforcement. A rewarding activity results in a release of dopamine from the brain’s ventral tegmental area (VTA). The pleasurable feelings that result give positive reinforcement, encouraging us to repeat the behaviour. Dopamine neurons in the VTA are also activated by certain drugs, which can lead to addiction.

The reward of catching a Pokémon activates the VTA, and acts as an incentive to continue hunting. Dr David Painter, a researcher at The University of Queensland, says the game’s business model leverages the psychology of positive reinforcement.

‘Pokémon Go is based on microtransactions,’ Painter says. While the game is free to download, users can purchase items to aid in the quest to catch ‘em all. Lure Modules, for example, can be set up to attract Pokémon to a particular Pokéstop, and certain restaurants have been using them to boost clientele. This model, Painter says, ‘conditions the spending of money with the reward of receiving more Pokémon,’ which can add up to be costly to the player (and lucrative for Niantic, the game’s developer).

Nostalgic for the ‘90s

The popularity of Pokémon Go is also no doubt fuelled by nostalgia, as Quentin Hardy has suggested in the New York Times. The game is ‘proof that millennials, for years the young generation, are getting old,’ he wrote. Millennials form the majority of app users, and are likely to recall playing with Pokémon cards or on Game Boy in the ‘90s.

Research into the neuroscience of nostalgia has found that reminiscing about positive past experiences rewards the brain. In one study, participants recalled memories while their brains were scanned. Participants who were asked to recall happy memories showed more activation in brain circuits that were also stimulated by monetary reward. The researchers suggested that, by reminding us of better times, nostalgia can function to improve mood.

Another study suggests that when a person feels lonely, nostalgia acts as a source of social connectedness and increases his or her perceived ability to emotionally support others. This finding is reinforced by the myriad anecdotal reports about the benefits of Pokémon Go to players’ mental health.

Virtual reality: the future of gaming

Previous research into the neuroscience of video games has found that certain games can improve cognitive function. Painter, whose PhD at the Queensland Brain Institute specialised in selective attention, says that action video games, for example, improve visual processing and attention. ‘Action video game players are faster able to detect a change at a particular location on the screen, and better able to reorient their attention.’

Specially designed video games could be used to improve attention in people with attention-deficit disorder, says Painter. The advent of virtual reality will revolutionise both gaming and education, he believes.

‘Pokémon Go is an example of augmented reality, where your computer is adding some information to make your everyday experience a little more fun,’ says Painter. ‘Complete virtual reality is set to hit the mainstream in 3 to 4 years,’ he says, citing Australian computer software company Euclideon a leader in the space.

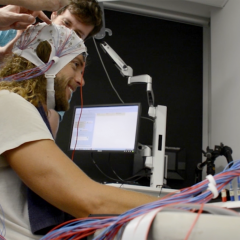

Brain–computer interfaces, which he and QBI colleagues are developing, and virtual reality can prepare people for real-world scenarios by training them in simulated but realistic environments. Improved flight simulators or hazard perception tests for drivers are two examples.

‘Pokémon Go is a genius idea,’ says Painter. The game is a taste of more to come. As technology and graphics improve, Painter says, the possibilities are endless. ‘It will improve our imaginations and not just reconstruct reality, but allow us to see and experience things we wouldn’t normally."

***

A version of this article appeared on Huffington Post Australia.